The 47 Ronin, Warriors of Ako, committed seppuku on this day, March 20.

Tag: samurai

The Last Samurai

While I am a big fan of the film, the last samurai, while watching it, there were a lot of parallels between history and real life, I was curious about the link and dug a little further. The Meji restoration in Japan was an interesting historical point in Japan’s history. The story of the last samurai also draws on those parallels.

I found the story of Jules Brunet. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Brunet

Jules Brunet was sent to Japan to train their military in Western tactics before fighting for the samurai against Meiji Imperialists during the Boshin War.

Not many people know the true story of The Last Samurai, the sweeping Tom Cruise epic of 2003. His character, the noble Captain Algren, was actually primarily based on a real person: the French officer Jules Brunet.

Brunet was sent to Japan to train soldiers on how to use modern weapons and tactics. He later chose to stay and fight alongside the Tokugawa samurai in their resistance against Emperor Meiji and his move to modernize Japan.

But how much of this reality is represented in the blockbuster?

The True Story Of The The Last Samurai: The Boshin War

Japan of the 19th century was an isolated nation. Contact with foreigners was largely suppressed. But everything changed in 1853 when American naval commander Matthew Perry appeared in Tokyo’s harbor with a fleet of modern ships.

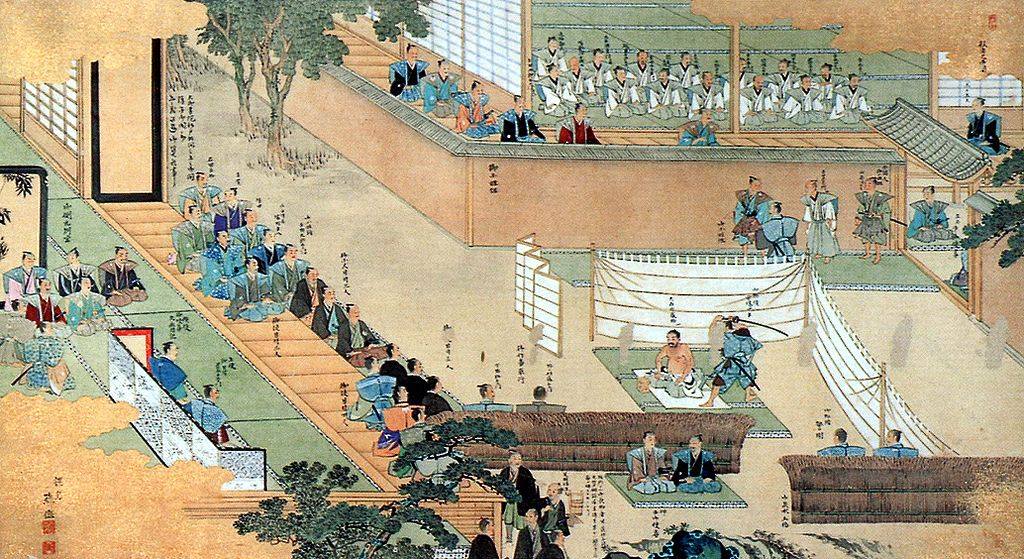

Wikimedia CommonsA painting of samurai rebel troops done by none other than Jules Brunet. Notice how the samurai have both western and traditional equipment, a point of the true story of The Last Samurai not explored in the movie.

For the first time ever, Japan was forced to open itself up to the outside world. The Japanese then signed a treaty with the U.S. the following year, the Kanagawa Treaty, which allowed American vessels to dock in two Japanese harbors. America also established a consul in Shimoda.

The event was a shock to Japan and consequently split its nation on whether it should modernize with the rest of the world or remain traditional. Thus followed the Boshin War of 1868-1869, also known as the Japanese Revolution, which was the bloody result of this split.

On one side was Japan’s Meiji Emperor, backed by powerful figures who sought to Westernize Japan and revive the emperor’s power. On the opposing side was the Tokugawa Shogunate, a continuation of the military dictatorship comprised of elite samurai which had ruled Japan since 1192.

Although the Tokugawa shogun, or leader, Yoshinobu, agreed to return power to the emperor, the peaceful transition turned violent when the Emperor was convinced to issue a decree that dissolved the Tokugawa house instead.

The Tokugawa shogun protested which naturally resulted in war. As it happens, 30-year-old French military veteran Jules Brunet was already in Japan when war broke out.

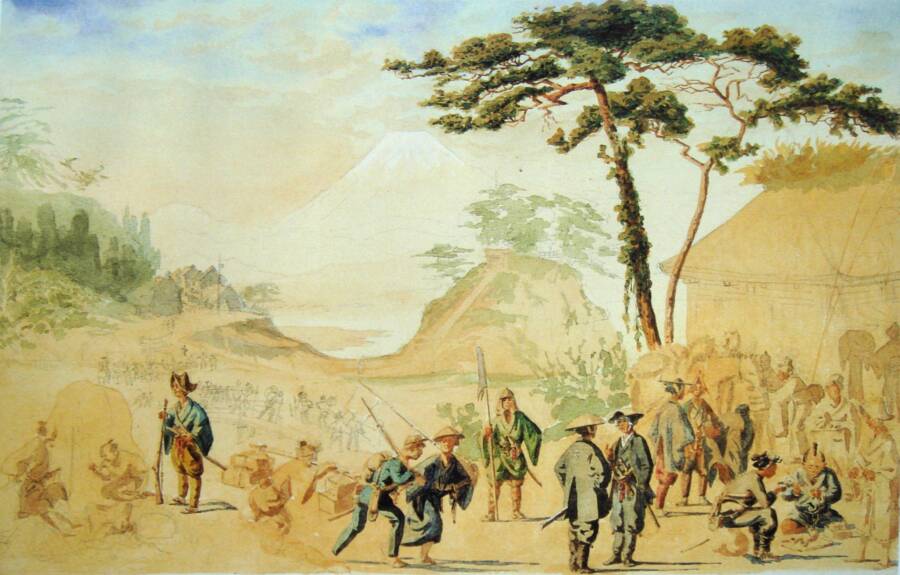

Wikimedia Commons Samurai of the Choshu clan during the Boshin War in late 1860s Japan.

Jules Brunet’s Role In The True Story Of The Last Samurai

Born on January 2, 1838, in Belfort, France, Jules Brunet followed a military career specializing in artillery. He first saw combat during the French intervention in Mexico from 1862 to 1864 where he was awarded the Légion d’honneur — the highest French military honor.

Wikimedia Commons Jules Brunet in full military dress in 1868.

Then, in 1867, Japan’s Tokugawa Shogunate requested help from Napoleon III’s Second French Empire in modernizing their armies. Brunet was sent as the artillery expert alongside a team of other French military advisors.

The group was to train the shogunate’s new troops on how to use modern weapons and tactics. Unfortunately for them, a civil war would break out just a year later between the shogunate and the imperial government.

On January 27, 1868, Brunet and Captain André Cazeneuve — another French military advisor in Japan — accompanied the shogun and his troops on a march to Japan’s capital city of Kyoto.

The shogun’s army was to deliver a stern letter to the Emperor to reverse his decision to strip the Tokugawa shogunate, or the longstanding elite, of their titles and lands.

However, the army was not allowed to pass and troops of the Satsuma and Choshu feudal lords — who were the influence behind the Emperor’s decree — were ordered to fire.

Thus began the first conflict of the Boshin War known as The Battle of Toba-Fushimi. Although the shogun’s forces had 15,000 men to the Satsuma-Choshu’s 5,000, they had one critical flaw: equipment.

While most of the imperial forces were armed with modern weapons such as rifles, howitzers, and Gatling guns, many of the shogunate’s soldiers were still armed with outdated weapons such as swords and pikes, as was the samurai custom.

The battle lasted for four days, but was a decisive victory for the imperial troops, leading many Japanese feudal lords to switch sides from the shogun to the emperor. Brunet and the Shogunate’s Admiral Enomoto Takeaki fled north to the capital city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) on the warship Fujisan.

Living With The Samurai

Around this time, foreign nations — including France — vowed neutrality in the conflict. Meanwhile, the restored Meiji Emperor ordered the French advisor mission to return home, since they had been training the troops of his enemy — the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Wikimedia Commons The full samurai battle regalia a Japanese warrior would wear to war. 1860.

While most of his peers agreed, Brunet refused. He chose to stay and fight alongside the Tokugawa. The only glimpse into Brunet’s decision comes from a letter he wrote directly to French Emperor Napoleon III. Aware that his actions would be seen as either insane or treasonous, he explained that:

“A revolution is forcing the Military Mission to return to France. Alone I stay, alone I wish to continue, under new conditions: the results obtained by the Mission, together with the Party of the North, which is the party favorable to France in Japan. Soon a reaction will take place, and the Daimyos of the North have offered me to be its soul. I have accepted, because with the help of one thousand Japanese officers and non-commissioned officers, our students, I can direct the 50,000 men of the confederation.

The Fall Of The Samurai

In Edo, the imperial forces were victorious again largely in part to Tokugawa Shogun Yoshinobu’s decision to submit to the Emperor. He surrendered the city and only small bands of shogunate forces continued to fight back.

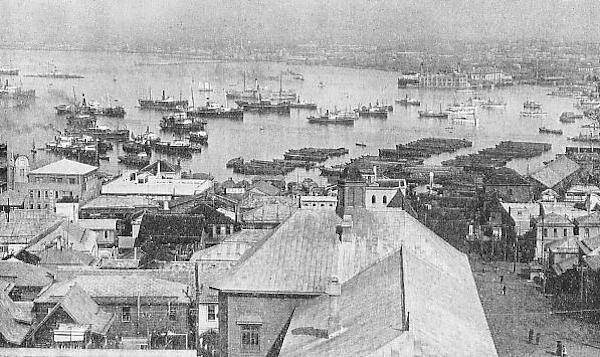

Wikimedia Commons The port of Hakodate in ca. 1930. The Battle of Hakodate saw 7,000 Imperial troops fight 3,000 shogun warriors in 1869.

Despite this, the commander of the shogunate’s navy, Enomoto Takeaki, refused to surrender and headed north in hopes to rally the Aizu clan’s samurai.

They became the core of the so-called Northern Coalition of feudal lords who joined the remaining Tokugawa leaders in their refusal to submit to the Emperor.

The Coalition continued to fight bravely against imperial forces in Northern Japan. Unfortunately, they simply didn’t have enough modern weaponry to stand a chance against the Emperor’s modernized troops. They were defeated by November 1868.

Around this time, Brunet and Enomoto fled north to the island of Hokkaido. Here, the remaining Tokugawa leaders established the Ezo Republic that continued their struggle against the Japanese imperial state.

By this point, it seemed as though Brunet had chosen the losing side, but surrender was not an option.

The last major battle of the Boshin War happened at the Hokkaido port city of Hakodate. In this battle that spanned half a year from December 1868 to June 1869, 7,000 Imperial troops battled against 3,000 Tokugawa rebels.

Wikimedia Commons French military advisors and their Japanese allies in Hokkaido. Back: Cazeneuve, Marlin, Fukushima Tokinosuke, Fortant. Front: Hosoya Yasutaro, Jules Brunet, Matsudaira Taro (vice-president of the Ezo Republic), and Tajima Kintaro.

Jules Brunet and his men did their best, but the odds were not in their favor, largely due to the technological superiority of the imperial forces.

Jules Brunet Escapes Japan

As a high-profile combatant of the losing side, Brunet was now a wanted man in Japan.

Fortunately, the French warship Coëtlogon evacuated him from Hokkaido just in time. He was then ferried to Saigon — at the time controlled by the French — and returned back to France.

Although the Japanese government demanded Brunet receive punishment for his support of the shogunate in the war, the French government did not budge because his story won the public’s support.

Instead, he was reinstated to the French Army after six months and participated in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, during which he was taken prisoner during the Siege of Metz.

Later on, he continued to play a major role in the French military, participating in the suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871.

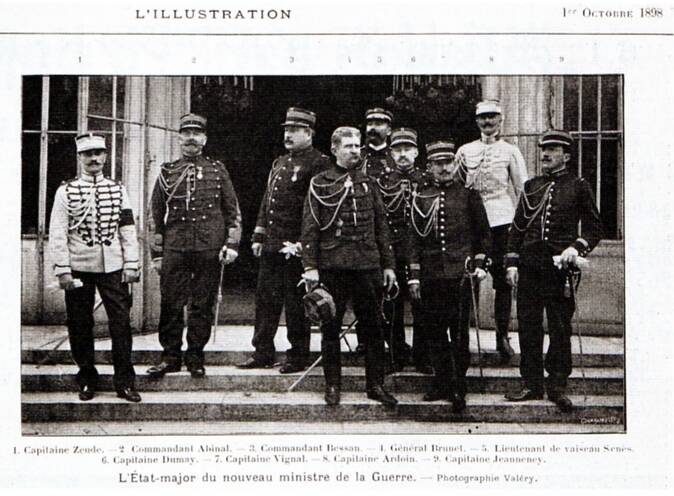

Wikimedia CommonsJules Brunet had a long, successful military career after his time in Japan. He’s seen here (hat in hand) as Chief of Staff. Oct. 1, 1898.

Meanwhile, his former friend Enomoto Takeaki was pardoned and rose to the rank of vice-admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, using his influence to get the Japanese government to not only forgive Brunet but award him a number of medals, including the prestigious Order of the Rising Sun.

Over the next 17 years, Jules Brunet himself was promoted several times. From officer to general, to Chief of Staff, he had a thoroughly successful military career until his death in 1911. But he would be most remembered as one of the key inspirations for the 2003 film The Last Samurai.

In this film, Tom Cruise plays American Army officer Nathan Algren, who arrives in Japan to help train Meiji government troops in modern weaponry but becomes embroiled in a war between the samurai and the Emperor’s modern forces.

There are many parallels between the story of Algren and Brunet.

Both were Western military officers who trained Japanese troops in the use of modern weapons and ended up supporting a rebellious group of samurai who still used mainly traditional weapons and tactics. Both also ended up being on the losing side.

But there are many differences as well. Unlike Brunet, Algren was training the imperial government troops and joins the samurai only after he becomes their hostage.

Further, in the film, the samurai are sorely overmatched against the Imperials in regards to equipment. In the true story of The Last Samurai, however, the samurai rebels did actually have some western garb and weaponry thanks to the Westerners like Brunet who had been paid to train them.

Meanwhile, the storyline in the film is based on a slightly later period in 1877 once the emperor was restored in Japan following the fall of the shogunate. This period was called the Meiji Restoration and it was the same year as the last major samurai rebellion against Japan’s imperial government.

Wikimedia Commons In the true story of The Last Samurai, this final battle which is depicted in the film and shows Katsumoto/Takamori’s death, did actually happen. But it happened years after Brunet left Japan.

This rebellion was organized by the samurai leader Saigo Takamori, who served as the inspiration for The Last Samurai‘s Katsumoto, played by Ken Watanabe. In the true story of The Last Samurai, Watanabe’s character who resembles Takamori leads a great and final samurai rebellion called the final battle of Shiroyama. In the film, Watanabe’s character Katsumoto falls and in reality, so did Takamori.

This battle, however, came in 1877, years after Brunet had already left Japan.

More importantly, the film paints the samurai rebels as the righteous and honorable keepers of an ancient tradition, while the Emperor’s supporters are shown as evil capitalists who only care about money.

As we know in reality, the real story of Japan’s struggle between modernity and tradition was far less black and white, with injustices and mistakes on both sides.

The Real Motivations Of The Samurai

According to history professor Cathy Schultz, “Many samurai fought Meiji modernization not for altruistic reasons but because it challenged their status as the privileged warrior caste…The film also misses the historical reality that many Meiji policy advisors were former samurai, who had voluntarily given up their traditional privileges to follow a course they believed would strengthen Japan.”

You can read more here: https://allthatsinteresting.com/last-samurai-true-story-jules-brunet