The hamburger is one of the world’s most popular foods, with nearly 50 billion served up annually in the United States alone. Although the humble beef-patty-on-a-bun is technically not much more than 100 years old, it’s part of a far greater lineage, linking American businessmen, World War II soldiers, German political refugees, medieval traders and Neolithic farmers.

The groundwork for the ground-beef sandwich was laid with the domestication of cattle (in Mesopotamia around 10,000 years ago), and with the growth of Hamburg, Germany, as an independent trading city in the 12th century, where beef delicacies were popular.

1121 – 1209 – Genghis Khan (1162-1227), crowned the “emperor of all emperors,” and his army of fierce Mongol horsemen, known as the “Golden Horde,” conquered two thirds of the then known world. The Mongols were a fast-moving, cavalry-based army that rode small sturdy ponies. They stayed in their saddles for long period of time, sometimes days without ever dismounting. They had little opportunity to stop and build a fire for their meal.

The entire village would follow behind the army on great wheeled carts they called “yurts,” leading huge herds of sheep, goats, oxen, and horses. As the army needed food that could be carried on their mounts and eaten easily with one hand while they rode, ground meat was the perfect choice. They would use scrapings of lamb or mutton which were formed into flat patties. They softened the meat by placing them under the saddles of their horses while riding into battle. When it was time to eat, the meat would be eaten raw, having been tenderized by the saddle and the back of the horse.

1238 – When Genghis Khan’s grandson, Khubilai Khan (1215-1294), invaded Moscow, they naturally brought their unique dietary ground meat with them. The Russians adopted it into their own cuisine with the name “Steak Tartare,” (Tartars being their name for the Mongols). Over many years, Russian chefs adapted and developed this dish and refining it with chopped onions and raw eggs.

5th Century

Beginning in the fifteenth century, minced beef was a valued delicacy throughout Europe. Hashed beef was made into sausage in several different regions of Europe.

1600s – Ships from the German port of Hamburg, Germany began calling on Russian port. During this period the Russian steak tartare was brought back to Germany and called “tartare steak.”

18th and 19th Centuries

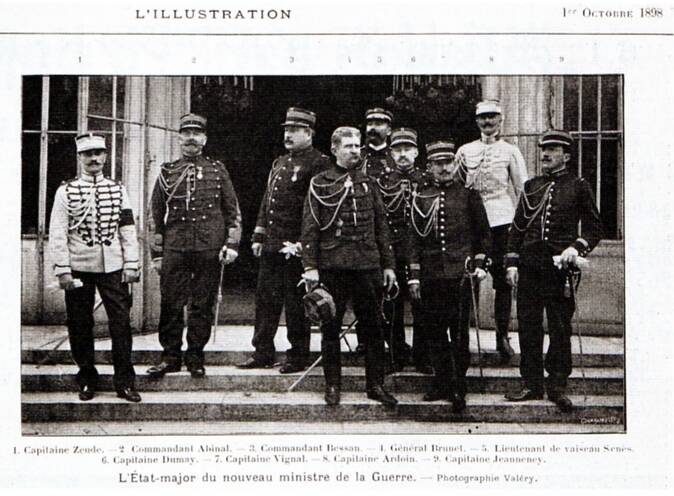

Jump ahead to 1848, when political revolutions shook the 39 states of the German Confederation, spurring an increase in German immigration to the United States. With German people came German food: beer gardens flourished in American cities, while butchers offered a panoply of traditional meat preparations. Because Hamburg was known as an exporter of high-quality beef, restaurants began offering a “Hamburg-style” chopped steak.

Hamburg Steak:

In the late eighteenth century, the largest ports in Europe were in Germany. Sailors who had visited the ports of Hamburg, Germany and New York, brought this food and term “Hamburg Steak” into popular usage. To attract German sailors, eating stands along the New York city harbor offered “steak cooked in the Hamburg style.”

Immigrants to the United States from German-speaking countries brought with them some of their favorite foods. One of them was Hamburg Steak. The Germans simply flavored shredded low-grade beef with regional spices, and both cooked and raw it became a standard meal among the poorer classes. In the seaport town of Hamburg, it acquired the name Hamburg steak. Today, this hamburger patty is no longer called Hamburg Steak in Germany but rather “Frikadelle,” “Frikandelle” or “Bulette,” orginally Italian and French words.

According to Theodora Fitzgibbon in her book The Food of the Western World – An Encyclopedia of food from North American and Europe:

The originated on the German Hamburg-Amerika line boats, which brought emigrants to America in the 1850s. There was at that time a famous Hamburg beef which was salted and sometimes slightly smoked, and therefore ideal for keeping on a long sea voyage. As it was hard, it was minced and sometimes stretched with soaked breadcrumbs and chopped onion. It was popular with the Jewish emigrants, who continued to make Hamburg steaks, as the patties were then called, with fresh meat when they settled in the U.S.

The cookbooks:

1758 – By the mid-18th century, German immigrants also begin arriving in England. One recipe, titled “Hamburgh Sausage,” appeared in Hannah Glasse’s 1758 English cookbook called The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. It consisted of chopped beef, suet, and spices. The author recommended that this sausage be served with toasted bread. Hannah Glasse’s cookbook was also very popular in Colonial America, although it was not published in the United States until 1805. This American edition also contained the “Hamburgh Sausage” recipe with slight revisions.

1844 – The original Boston Cooking School Cook Book, by Mrs. D.A. Lincoln (Mary Bailey), 1844 had a recipe for Broiled Meat Cakes and also Hamburgh Steak:

Broiled Meat Cakes – Chop lean, raw beef quite fine. Season with salt, pepper, and a little chopped onion, or onion juice. Make it into small flat cakes, and broil on a well-greased gridiron or on a hot frying pan. Serve very hot with butter or Maitre de’ Hotel sauce.

Hamburgh Steak – Pound a slice of round steak enough to break the fibre. Fry two or three onions, minced fine, in butter until slightly browned. Spread the onions over the meat, fold the ends of the meat together, and pound again, to keep the onions in the middle. Broil two or three minutes. Spread with butter, salt, and pepper.

1894 – In the 1894 edition of the book The Epicurean: A Complete Treatise of Analytical & Practical Studies, by Charles Ranhofer (1836-1899), chef at the famous Delmonico’s restaurant in New York, there is a listing for Beef Steak Hamburg Style. The dish is also listed in French as Bifteck Hambourgeoise. What made his version unique was that the recipe called for the ground beef to be mixed with kidney and bone marrow:

One pound of tenderloin beef free of sinews and fat; chop it up on a chopping block with four ounces of beef kidney suet, free of nerves and skin or else the same quantity of marrow; add one ounce of chopped onions fried in butter without attaining color; season all with salt, pepper and nutmeg, and divide the preparation into balls, each one weighing four ounces; flatten them down, roll them in bread-crumbs and fry them in a sautpan in butter. When of a fine color on both sides, dish them up pouring a good thickened gravy . . . over.”

1906 – Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), American novelist, wrote in his book called The Jungle, which told of the horrors of Chicago meat packing plants. This book caused much distrust in the United States regarding chopped meat. Sinclair was surprised that the public missed the main point of his impressionistic fiction and took it to be an indictment of unhygienic conditions of the meat packing industry. This caused people to not trust chopped meat for several years.

Invention of Meat Choppers:

Referring to ground beef as hamburger dates to the invention of the mechanical meat choppers during the 1800s. It was not until the early nineteenth century that wood, tin, and pewter cylinders with wooden plunger pushers became common. Steve Church of Ridgecrest, California uncovered some long forgotten U. S. patents on Meat Cutters:

In mid-19th-century America, preparations of raw beef that had been chopped, chipped, ground or scraped were a common prescription for digestive issues. After a New York doctor, James H. Salisbury suggested in 1867 that cooked beef patties might be just as healthy, cooks and physicians alike quickly adopted the “Salisbury Steak”. Around the same time, the first popular meat grinders for home use became widely available (Salisbury endorsed one called the American Chopper) setting the stage for an explosion of readily available ground beef.

The hamburger seems to have made its jump from plate to bun in the last decades of the 19th century, though the site of this transformation is highly contested. Lunch wagons, fair stands and roadside restaurants in Wisconsin, Connecticut, Ohio, New York and Texas have all been put forward as possible sites of the hamburger’s birth. Whatever its genesis, the burger-on-a-bun found its first wide audience at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, which also introduced millions of Americans to new foods ranging from waffle ice cream cones and cotton candy to peanut butter and iced tea.

Two years later, though, disaster struck in the form of Upton Sinclair’s journalistic novel The Jungle, which detailed the unsavory side of the American meatpacking industry. Industrial ground beef was easy to adulterate with fillers, preservatives and meat scraps, and the hamburger became a prime suspect.

The history of the American burger:

The hamburger might have remained on the seamier margins of American cuisine were it not for the vision of Edgar “Billy” Ingram and Walter Anderson, who opened their first White Castle restaurant in Kansas in 1921. Sheathed inside and out in gleaming porcelain and stainless steel, White Castle countered hamburger meat’s low reputation by becoming bastions of cleanliness, health and hygiene (Ingram even commissioned a medical school study to show the health benefits of hamburgers). His system, which included on-premise meat grinding, worked well and was the inspiration for other national hamburger chains founded in the boom years after World War II: McDonald’s and In-N-Out Burger (both founded in 1948), Burger King (1954) and Wendy’s (1969).

Only one of the claimants below served their hamburgers on a bun – Oscar Weber Bilby in 1891. The rest served them as sandwiches between two slices of bread.

Most of the following stories on the history of the hamburgers were told after the fact and are based on the recollections of family members. For many people, which story or legend you believe probably depends on where you are from. You be the judge! The claims are as follows:

1885 – Charlie Nagreen of Seymour, Wisconsin – At the age of 15, he sold hamburgers from his ox-drawn food stand at the Outagamie County Fair. He went to the Outagamie County Fair and set up a stand selling meatballs. Business wasn’t good and he quickly realized that it was because meatballs were too difficult to eat while strolling around the fair. In a flash of innovation, he flattened the meatballs, placed them between two slices of bread and called his new creation a hamburger. He was known to many as “Hamburger Charlie.” He returned to sell hamburgers at the fair every year until his death in 1951, and he would entertain people with guitar and mouth organ and his jingle:

Hamburgers, hamburgers, hamburgers hot; onions in the middle, pickle on top. Makes your lips go flippity flop.

The town of Seymour, Wisconsin is so certain about this claim that they even have a Hamburger Hall of Fame that they built as a tribute to Charlie Nagreen and the legacy he left behind. The town claims to be “Home of the Hamburger” and holds an annual Burger Festival on the first Saturday of August each year. Events include a ketchup slide, bun toss, and hamburger-eating contest, as well as the “world’s largest hamburger parade.”

On May 9, 2007, members of the Wisconsin legislature declared Seymour, Wisconsin, as the home of the hamburger:

Whereas, Seymour, Wisconsin, is the right home of the hamburger; and,

Whereas, other accounts of the origination of the hamburger trace back only so far as the 1880s, while Seymour’s claim can be traced to 1885; and,

Whereas, Charles Nagreen, also known as Hamburger Charlie, of Seymour, Wisconsin, began calling ground beef patties in a bun “hamburgers” in 1885; and,

Whereas, Hamburger Charlie first sold his world-famous hamburgers at age 15 at the first Seymour Fair in 1885, and later at the Brown and Outagamie county fairs; and,

Whereas, Hamburger Charlie employed as many as eight people at his famous hamburger tent, selling 150 pounds of hamburgers on some days; and,

Whereas, the hamburger has since become an American classic, enjoyed by families and backyard grills alike; now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the assembly, the senate concurring, That the members of the Wisconsin legislature declare Seymour, Wisconsin, the Original Home of the Hamburger.

1885 – The family of Frank and Charles Menches from Akron, Ohio, claim the brothers invented the hamburger while traveling in a 100-man traveling concession circuit at events (fairs, race meetings, and farmers’ picnics) in the Midwest in the early 1880s. During a stop at the Erie County Fair in Hamburg, New York, the brothers ran out of pork for their hot sausage patty sandwiches. Because this happened on a particularly hot day, the local butchers stop slaughtering pigs. The butcher suggested that they substitute beef for the pork. The brothers ground up the beef, mixed it with some brown sugar, coffee, and other spices and served it as a sandwich between two pieces of bread. They called this sandwich the “hamburger” after Hamburg, New York where the fair was being held. According to family legend, Frank didn’t really know what to call it, so he looked up and saw the banner for the Hamburg fair and said, “This is the hamburger.” In Frank’s 1951 obituary in The Los Angeles Times, he is acknowledged him as the ”inventor” of the hamburger.

Hamburg held its first Burgerfest in 1985 to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of the hamburger after organizers discovered a history book detailing the burger’s origins.

In 1991, Menches and his siblings stumbled across the original recipe among some old papers their great-grandmother left behind. After selling their burgers at county fairs for a few years, the family opened up the Menches Bros. Restaurant in Akron, Ohio. The Menches family is still in the restaurant business and still serving hamburgers in Ohio.

On May 28, 2005, the town of Akron, Ohio hosted the First Annual National Hamburger Festival to celebrate the 120th Anniversary of the invention of the hamburger. The festival will be dedicated to Frank and Charles Menches. That is how sure the city of Akron is on the Menches’ family claim on the contested contention that two residents invented the hamburger. The Ohio legislature is also considering making hamburgers the state food.

1891 – The family of Oscar Weber Bilby claim the first-known hamburger on a bun was served on Grandpa Oscar’s farm just west of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1891. The family says that Grandpa Oscar was the first to add the bun, but they concede that hamburger sandwiches made with bread may predate Grandpa Oscar’s famous hamburger.

Michael Wallis, travel writer and reporter for Oklahoma Today magazine, did an extensive search in 1995 for the true origins of the hamburger and determined that Oscar Weber Bilby himself was the creator of the hamburger as we know it. According to Wallis’s 1995 article, Welcome To Hamburger Heaven, in an interview with Harold Bilby:

The story has been passed down through the generations like a family Bible. “Grandpa himself told me that it was in June of 1891 when he took up a chunk of iron and made himself a big ol’ grill,” explains Harold. “Then the next month on the Fourth of July he built a hickory wood fire underneath that grill, and when those coals were glowing hot, he took some ground Angus meat and fired up a big batch of hamburgers. When they were cooked all good and juicy, he put them on my Grandma Fanny’s homemade yeast buns – the best buns in all the world, made from her own secret recipe. He served those burgers on buns to neighbors and friends under a grove of pecan trees . . . They couldn’t get enough, so Grandpa hosted another big feed. He did that every Fourth of July, and sometimes as many as 125 people showed up.”

Simple math supports Harold Bilby’s contention that if his Grandpa served burgers on Grandma Fanny’s buns in 1891, then the Bilbys eclipsed the St. Louis World’s Fair vendors by at least thirteen years. That would make Oklahoma the cradle of the hamburger. “There’s not even the trace of a doubt in my mind,” say Harold. “My grandpa invented the hamburger on a bun right here in what became Oklahoma, and if anybody wants to say different, then let them prove otherwise.”

In 1933, Oscar and his son, Leo, opened the family’s first hamburger stand in Tulsa, Oklahoma, called Weber’s Superior Root Beer Stand. They still use the same grill used in 1891, with one minor variation, the wood stove has been converted to natural gas. In a letter to me, Linda Stradley, dated July 31, 2004, Rick Bilby states the following:

My great-grandfather, Oscar Weber Bilby invented the hamburger on July 4, 1891. He served ground beef patties that were seared to perfection on a open flame from a hand-made grill. My great-grandmother Fanny made her own home-made yeast hamburger buns to put around the ground beef patties. They served this new sandwich along with their tasty home-made rood beer which was also carbonated with yeast. People would come for all over the county on July 4th each year to consume and enjoy these treats. To this day we still cook our hamburger on grandpa’s grill, which is now fired by natural gas.

On April 13, 1995, Governor Frank Keating of Oklahoma proclaimed that the real birthplace of the hamburger on the bun, was created and consumed in Tulsa in 1891. The State of Oklahoma Proclamation states:

Whereas, scurrilous rumors have credited Athens, Texas, as the birthplace of the hamburger, claiming for that region south of the Red River commonly known as Baja Oklahoma a fame and renown which are hardly its due; and

Whereas, the Legislature of Baja Oklahoma has gone so far as to declare April 3, 1995, to be Athens Day at the State Capitol, largely on the strength of this bogus claim, and

Whereas, while the residents, the scenery, the hospitality and the food found in Athens are no doubt superior to those in virtually any other locale, they must be recognized. In the words of Mark Twain, as “the lightning bug is to the lightning” when compared with the Great City of Tulsa in the Great State of Oklahoma; and

Whereas, although someone in Athens, in the 1860’s, may have place cooked ground beef between two slices of bread, this minor accomplishment can in no way be regarded comes on a bun accompanied by such delight as pickles, onions, lettuce, tomato, cheese and, in some cases, special sauce; and

Whereas, the first true hamburger on a bun, as meticulous research shows, was created and consumed in Tulsa in 1891 and was only copied for resale at the St. Louis World’s Fair a full 13 years after that momentous and history-making occasion:

Now Therefore, I, Frank Keating, Governor of the State of Oklahoma, do hereby proclaim April 12, 1995, as THE REAL BIRTHPLACE OF THE HAMBURGER IN TULSA DAY.

1900 – Louis Lassen of New Haven, Connecticut is also recorded as serving the first “burger” at his New Haven luncheonette called Louis’ Lunch Wagon. Louis ran a small lunch wagon selling steak sandwiches to local factory workers. A frugal business man, he did not like to waste the excess beef from his daily lunch rush. It is said that he ground up some scraps of beef and served it as a sandwich, the sandwich was sold between pieces of toasted bread, to a customer who was in a hurry and wanted to eat on the run.

Kenneth Lassen, Louis’ grandson, was quoted in the September 25, 1991 Athens Daily Review as saying;

“We have signed, dated and notarized affidavits saying we served the first hamburger sandwiches in 1900. Other people may have been serving the steak but there’s a big difference between a hamburger steak and a hamburger sandwich.”

In the mid-1960s, the New Haven Preservation Trust placed a plaque on the building where Louis’ Lunch is located proclaiming Louis’ Lunch to be the first place the hamburger was sold.

Louis’ Lunch is still selling their hamburgers from a small brick building in New Haven. The sandwich is grilled vertically in antique gas grills and served between pieces of toast rather than a bun, and refuse to provide mustard or ketchup.

Library of Congress named Louis’ Lunch a “Connecticut Legacy.” The following is taken from the Congressional Record, 27 July 2000, page E1377:

Honoring Louis’ Lunch on Its 105th Anniversary – Representative Rosa L. DeLauro:

. . . it is with great pleasure that I rise today to celebrate the 105th anniversary of a true New Haven landmark: Louis’ Lunch. Recently the Lassen family celebrated this landmark as well as the 100th anniversary of their claim to fame — the invention and commercial serving of one of America’s favorites, the hamburger . . . The Lassens and the community of New Haven shared unparalleled excitement when the Library of Congress named Louis’ Lunch a “Connecticut Legacy” — nothing could be more true.

1901 or 1902 – Bert W. Gary of Clarinda, Iowa, in an article by Paige Carlin for the Omaha World Herald newspaper, takes no credit for having invented it, but he stakes uncompromising claim to being the “daddy” of the hamburger industry. He served his hamburger on a bun:

The hamburger business all started about 1901 or 1902 (The Grays aren’t sure which) when Mr. Gray operated a little cafe on the east side of Clarinda’s Courthouse Square.

Mr. Gray recalled: “There was an old German here named Ail Wall (or Wahl, maybe) and he ran a butcher shop. One day he was stuffing bologna with a little hand machine, and he said to me: ‘Bert, why wouldn’t ground meat make a good sandwich?’”

“I said I’d try it, so I took this ground beef and mixed it with an egg batter and fried it. I couldn’t bet anybody to eat it. I quit the egg batter and just took the meat with a little flour to hold it together. The new technique paid off.”

“He almost ran the other cafes out of the sandwich business,” Mrs. Gray put in. “He could make hamburgers so nice and soft and juicy – better than I ever could,” she added.

“This old German, Wall, came over here from Hamburg, and that’s what he said to call it,” Mr. Gray explained. “I sold them for a nickel apiece in those days. That was when the meat was 10 or 12 cents a pound,” he added. “I bought $5 or $6 worth of meat at a time and I got three or four dozen pans of buns from the bakery a day.”

One time the Grays heard a conflicting claim by a man (somewhere in the northern part of the state) that he was the hamburger’s inventor. “I didn’t pay any attention to him,” Mr. Gray snorted. “I’ve got plenty of proof mine was the first,” he said.

so much more to read at https://whatscookingamerica.net/history/hamburgerhistory.htm