In 1961, it officially became illegal to give someone a tattoo in New York City. But Thom deVita didn’t let this new restriction deter him from inking people. This ban existed till 1997.

What is the earliest evidence of tattoos?

In terms of tattoos on actual bodies, the earliest known examples were for a long time Egyptian and were present on several female mummies dated to c. 2000 B.C. But following the more recent discovery of the Iceman from the area of the Italian-Austrian border in 1991 and his tattoo patterns, this date has been pushed back a further thousand years when he was carbon-dated at around 5,200 years old.

Can you describe the tattoos on the Iceman and their significance?

Following discussions with my colleague Professor Don Brothwell of the University of York, one of the specialists who examined him, the distribution of the tattooed dots and small crosses on his lower spine and right knee and ankle joints correspond to areas of strain-induced degeneration, with the suggestion that they may have been applied to alleviate joint pain and were therefore essentially therapeutic. This would also explain their somewhat ‘random’ distribution in areas of the body which would not have been that easy to display had they been applied as a form of status marker.

What is the evidence that ancient Egyptians had tattoos?

There’s certainly evidence that women had tattoos on their bodies and limbs from figurines c. 4000-3500 B.C. to occasional female figures represented in tomb scenes c. 1200 B.C. and in figurine form c. 1300 B.C., all with tattoos on their thighs. Also small bronze implements identified as tattooing tools were discovered at the town site of Gurob in northern Egypt and dated to c. 1450 B.C. And then, of course, there are the mummies with tattoos, from the three women already mentioned and dated to c. 2000 B.C. to several later examples of female mummies with these forms of permanent marks found in Greco-Roman burials at Akhmim.

What function did these tattoos serve? Who got them and why?

Because this seemed to be an exclusively female practice in ancient Egypt, mummies found with tattoos were usually dismissed by the (male) excavators who seemed to assume the women were of “dubious status,” described in some cases as “dancing girls.” The female mummies had nevertheless been buried at Deir el-Bahari (opposite modern Luxor) in an area associated with royal and elite burials, and we know that at least one of the women described as “probably a royal concubine” was actually a high-status priestess named Amunet, as revealed by her funerary inscriptions.

And although it has long been assumed that such tattoos were the mark of prostitutes or were meant to protect the women against sexually transmitted diseases, I personally believe that the tattooing of ancient Egyptian women had a therapeutic role and functioned as a permanent form of amulet during the very difficult time of pregnancy and birth. This is supported by the pattern of distribution, largely around the abdomen, on top of the thighs and the breasts, and would also explain the specific types of designs, in particular the net-like distribution of dots applied over the abdomen. During pregnancy, this specific pattern would expand in a protective fashion in the same way bead nets were placed over wrapped mummies to protect them and “keep everything in.” The placing of small figures of the household deity Bes at the tops of their thighs would again suggest the use of tattoos as a means of safeguarding the actual birth, since Bes was the protector of women in labor, and his position at the tops of the thighs a suitable location. This would ultimately explain tattoos as a purely female custom.

Who made the tattoos?

Although we have no explicit written evidence in the case of ancient Egypt, it may well be that the older women of a community would create the tattoos for the younger women, as happened in 19th-century Egypt and happens in some parts of the world today.

What instruments did they use?

It is possible that an implement best described as a sharp point set in a wooden handle, dated to c. 3000 B.C. and discovered by archaeologist W.M.F. Petrie at the site of Abydos may have been used to create tattoos. Petrie also found the aforementioned set of small bronze instruments c. 1450 B.C.—resembling wide, flattened needles—at the ancient town site of Gurob. If tied together in a bunch, they would provide repeated patterns of multiple dots.

These instruments are also remarkably similar to much later tattooing implements used in 19th-century Egypt. The English writer William Lane (1801-1876) observed, “the operation is performed with several needles (generally seven) tied together: with these the skin is pricked in a desired pattern: some smoke black (of wood or oil), mixed with milk from the breast of a woman, is then rubbed in…. It is generally performed at the age of about 5 or 6 years, and by gipsy-women.”

What did these tattoos look like?

Most examples on mummies are largely dotted patterns of lines and diamond patterns, while figurines sometimes feature more naturalistic images. The tattoos occasionally found in tomb scenes and on small female figurines which form part of cosmetic items also have small figures of the dwarf god Bes on the thigh area.

What were they made of? How many colors were used?

Usually a dark or black pigment such as soot was introduced into the pricked skin. It seems that brighter colors were largely used in other ancient cultures, such as the Inuit who are believed to have used a yellow color along with the more usual darker pigments.

What has surprised you the most about ancient Egyptian tattooing?

That it appears to have been restricted to women during the purely dynastic period, i.e. pre-332 B.C. Also the way in which some of the designs can be seen to be very well placed, once it is accepted they were used as a means of safeguarding women during pregnancy and birth.

Can you describe the tattoos used in other ancient cultures and how they differ?

Among the numerous ancient cultures who appear to have used tattooing as a permanent form of body adornment, the Nubians to the south of Egypt are known to have used tattoos. The mummified remains of women of the indigenous C-group culture found in cemeteries near Kubban c. 2000-15000 B.C. were found to have blue tattoos, which in at least one case featured the same arrangement of dots across the abdomen noted on the aforementioned female mummies from Deir el-Bahari. The ancient Egyptians also represented the male leaders of the Libyan neighbors c. 1300-1100 B.C. with clear, rather geometrical tattoo marks on their arms and legs and portrayed them in Egyptian tomb, temple and palace scenes.

The Scythian Pazyryk of the Altai Mountain region were another ancient culture which employed tattoos. In 1948, the 2,400 year old body of a Scythian male was discovered preserved in ice in Siberia, his limbs and torso covered in ornate tattoos of mythical animals. Then, in 1993, a woman with tattoos, again of mythical creatures on her shoulders, wrists and thumb and of similar date, was found in a tomb in Altai. The practice is also confirmed by the Greek writer Herodotus c. 450 B.C., who stated that amongst the Scythians and Thracians “tattoos were a mark of nobility, and not to have them was testimony of low birth.”

Accounts of the ancient Britons likewise suggest they too were tattooed as a mark of high status, and with “divers shapes of beasts” tattooed on their bodies, the Romans named one northern tribe “Picti,” literally “the painted people.”

Yet amongst the Greeks and Romans, the use of tattoos or “stigmata” as they were then called, seems to have been largely used as a means to mark someone as “belonging” either to a religious sect or to an owner in the case of slaves or even as a punitive measure to mark them as criminals. It is therefore quite intriguing that during Ptolemaic times when a dynasty of Macedonian Greek monarchs ruled Egypt, the pharaoh himself, Ptolemy IV (221-205 B.C.), was said to have been tattooed with ivy leaves to symbolize his devotion to Dionysus, Greek god of wine and the patron deity of the royal house at that time. The fashion was also adopted by Roman soldiers and spread across the Roman Empire until the emergence of Christianity, when tattoos were felt to “disfigure that made in God’s image” and so were banned by the Emperor Constantine (A.D. 306-373).

We have also examined tattoos on mummified remains of some of the ancient pre-Columbian cultures of Peru and Chile, which often replicate the same highly ornate images of stylized animals and a wide variety of symbols found in their textile and pottery designs. One stunning female figurine of the Naszca culture has what appears to be a huge tattoo right around her lower torso, stretching across her abdomen and extending down to her genitalia and, presumably, once again alluding to the regions associated with birth. Then on the mummified remains which have survived, the tattoos were noted on torsos, limbs, hands, the fingers and thumbs, and sometimes facial tattooing was practiced.

With extensive facial and body tattooing used among Native Americans, such as the Cree, the mummified bodies of a group of six Greenland Inuit women c. A.D. 1475 also revealed evidence for facial tattooing. Infrared examination revealed that five of the women had been tattooed in a line extending over the eyebrows, along the cheeks and in some cases with a series of lines on the chin. Another tattooed female mummy, dated 1,000 years earlier, was also found on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea, her tattoos of dots, lines and hearts confined to the arms and hands.

Evidence for tattooing is also found amongst some of the ancient mummies found in China’s Taklamakan Desert c. 1200 B.C., although during the later Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-A.D. 220), it seems that only criminals were tattooed.

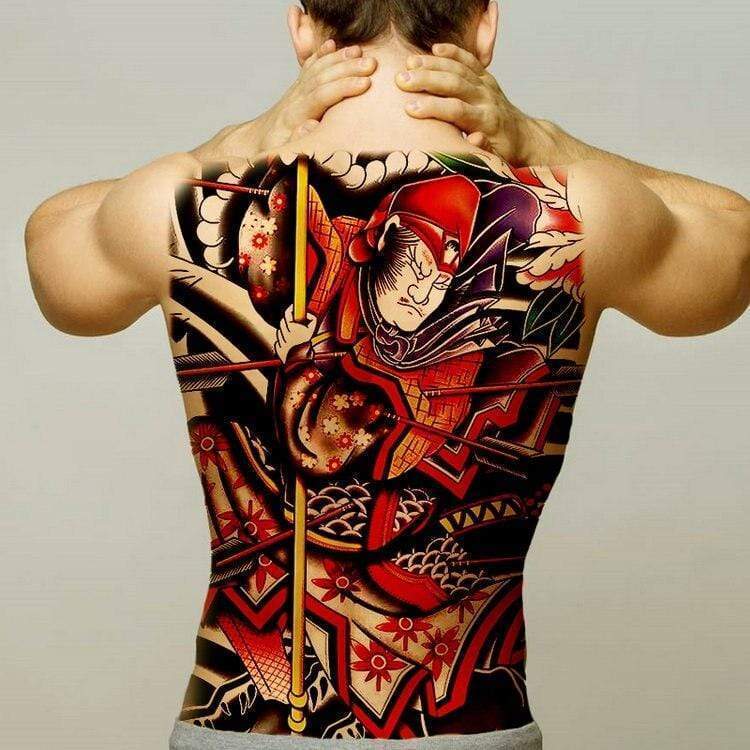

Japanese men began adorning their bodies with elaborate tattoos in the late A.D. 3rd century.

The elaborate tattoos of the Polynesian cultures are thought to have developed over millennia, featuring highly elaborate geometric designs, which in many cases can cover the whole body. Following James Cook’s British expedition to Tahiti in 1769, the islanders’ term “tatatau” or “tattau,” meaning to hit or strike, gave the west our modern term “tattoo.” The marks then became fashionable among Europeans, particularly so in the case of men such as sailors and coal-miners, with both professions which carried serious risks and presumably explaining the almost amulet-like use of anchors or miner’s lamp tattoos on the men’s forearms.

What about modern tattoos outside of the western world?

Modern Japanese tattoos are real works of art, with many modern practioners, while the highly skilled tattooists of Samoa continue to create their art as it was carried out in ancient times, prior to the invention of modern tattooing equipment. Various cultures throughout Africa also employ tattoos, including the fine dots on the faces of Berber women in Algeria, the elaborate facial tattoos of Wodabe men in Niger and the small crosses on the inner forearms which mark Egypt’s Christian Copts.

What do Maori facial designs represent?

In the Maori culture of New Zealand, the head was considered the most important part of the body, with the face embellished by incredibly elaborate tattoos or ‘moko,’ which were regarded as marks of high status. Each tattoo design was unique to that individual and since it conveyed specific information about their status, rank, ancestry and abilities, it has accurately been described as a form of id card or passport, a kind of aesthetic bar code for the face. After sharp bone chisels were used to cut the designs into the skin, a soot-based pigment would be tapped into the open wounds, which then healed over to seal in the design. With the tattoos of warriors given at various stages in their lives as a kind of rite of passage, the decorations were regarded as enhancing their features and making them more attractive to the opposite sex.

Although Maori women were also tattooed on their faces, the markings tended to be concentrated around the nose and lips. Although Christian missionaries tried to stop the procedure, the women maintained that tattoos around their mouths and chins prevented the skin becoming wrinkled and kept them young; the practice was apparently continued as recently as the 1970s.

Why do you think so many cultures have marked the human body and did their practices influence one another?

In many cases, it seems to have sprung up independently as a permanent way to place protective or therapeutic symbols upon the body, then as a means of marking people out into appropriate social, political or religious groups, or simply as a form of self-expression or fashion statement.

Yet, as in so many other areas of adornment, there was of course cross-cultural influences, such as those which existed between the Egyptians and Nubians, the Thracians and Greeks and the many cultures encountered by Roman soldiers during the expansion of the Roman Empire in the final centuries B.C. and the first centuries A.D. And, certainly, Polynesian culture is thought to have influenced Maori tattoos.

As reports and images from European explorers’ travels in Polynesia reached Europe, the modern fascination with tattoos began to take hold. Although the ancient peoples of Europe had practiced some forms of tattooing, it had disappeared long before the mid-1700s. Explorers returned home with tattooed Polynesians to exhibit at world fairs, in lecture halls and in dime museums, to demonstrate the height of European civilization compared to the “primitive natives” of Polynesia. But the sailors on their ships also returned home with their own tattoos.

Native practitioners found an eager clientele among sailors and others visitors to Polynesia. Colonial ideology dictated that the tattoos of the Polynesians were a mark of their primitiveness. The mortification of their skin and the ritual of spilling blood ran contrary to the values and beliefs of European missionaries, who largely condemned tattoos. Although many forms of traditional Polynesian tattoo declined sharply after the arrival of Europeans, the art form, unbound from tradition, flourished on the fringes of European society.

In the United States, technological advances in machinery, design and color led to a unique, all-American, mass-produced form of tattoo. Martin Hildebrandt set up a permanent tattoo shop in New York City in 1846 and began a tradition by tattooing sailors and military servicemen from both sides of the Civil War. In England, youthful King Edward VII started a tattoo fad among the aristocracy when he was tattooed before ascending to the throne. Both these trends mirror the cultural beliefs that inspired Polynesian tattoos: to show loyalty and devotion, to commemorate a great feat in battle, or simply to beautify the body with a distinctive work of art.

The World War II era of the 1940s was considered the Golden Age of tattoo due to the patriotic mood and the preponderance of men in uniform. But would-be sailors with tattoos of naked women weren’t allowed into the navy and tattoo artists clothed many of them with nurses’ dresses, Native-American costumes or the like during the war. By the 1950s, tattooing had an established place in Western culture, but was generally viewed with distain by the higher reaches of society. Back alley and boardwalk tattoo parlors continued to do brisk business with sailors and soldiers. But they often refused to tattoo women unless they were twenty-one, married and accompanied by their spouse, to spare tattoo artists the wrath of a father, boyfriend or unwitting husband.

|

|

|

Today tattooing is recognized as a legitimate art form.

|

Today, tattooing is recognized as a legitimate art form that attracts people of all walks of life and both sexes. Each individual has his or her own reasons for getting a tattoo; to mark themselves as a member a group, to honor loved ones, to express an image of themselves to others. With the greater acceptance of tattoos in the West, many tattoo artists in Polynesia are incorporating ancient symbols and patterns into modern designs. Others are using the technical advances in tattooing to make traditional tattooing safer and more accessible to Polynesians who want to identify themselves with their culture’s past.

Humans have marked their bodies with tattoos for thousands of years. These permanent designs—sometimes plain, sometimes elaborate, always personal—have served as amulets, status symbols, declarations of love, signs of religious beliefs, adornments and even forms of punishment. Joann Fletcher, research fellow in the department of archaeology at the University of York in Britain, describes the history of tattoos and their cultural significance to people around the world, from the famous ” Iceman,” a 5,200-year-old frozen mummy, to today’s Maori.

Source:

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/tattoos-144038580/

- https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/beyond.html

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/tattoos-were-illegal-new-york-city-exhibition-180962232/